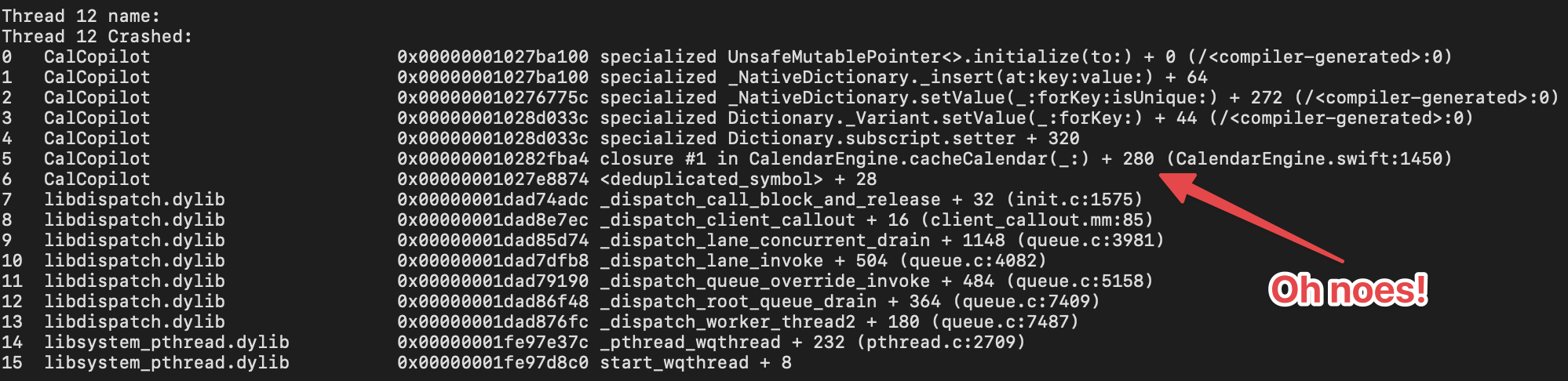

It started, as these things often do, with a crash report. An EXC_BAD_ACCESS null pointer dereference in CalCopilot's caching layer, appearing after days of background execution. The kind of crash that only shows up in the real world, never in development, because that would be way too easy.

I'd been building this app, a calendar automation tool for iOS, for several months. I launched last month, users were using it, and things were going well. Most importantly it was solving my own calendar syncing problems.

Looking at the stack trace, I could see the problem: two threads accessing a dictionary simultaneously. A classic data race. One thread was reading, another was writing, and the result was chaos. The fix seemed straightforward at first: add a lock around the dictionary access. But this is where my journey into Swift 6 concurrency began, I wanted to elimiate entire classes of concurrency bugs.

Background: Swift 6 Concurrency

Swift 6 introduced compile-time data race safety. The compiler can now verify, at build time, that your code doesn't contain data races. In most languages, concurrency bugs are discovered through testing (if you're lucky), Thread Sanitizer runs (if you remember), or production crashes (if you're me). Swift 6 shifts this detection earlier, catching whole classes of issues before you ship.

Here's some good resources on Swift 6 and the Swift Concurrency model:

- Understanding and Using

@MainActorin SwiftUI - A good intro to the@MainActorconcept - Apple's Adopting Swift 6 Guide — The official documentation with practical migration patterns

- Swift.org Migration Guide — Comprehensive guide covering incremental adoption strategies

How Not to Migrate (the first attempt)

After reading about Swift 6's concurrency, I was excited. The crash report was still fresh in my mind, and here was a way to prevent not just that bug, but an entire category of bugs. So I did what any enthusiastic developer would do: I enabled Swift 6 mode and strict concurrency "minimal" checking and ran a build in Xcode.

The compiler immediately spit out 76 errors and 238 warnings.

Here's a representative sample:

CalCopilotTests/Services/CalendarEngineTests.swift:907:15: error:

call to main actor-isolated instance method 'waitForScreen()'

in a synchronous nonisolated contextCalCopilot/Core/Services/BackgroundTaskManager.swift:786:24: error:

sending 'self' risks causing data racesCalCopilot/Core/Services/CoreDataActivityLogRepository.swift:45:15: error:

capture of 'self' with non-Sendable type 'CoreDataActivityLogRepository'

in a @Sendable closureThe problem wasn't just the number of errors. It's how fixing one of them causes a cascade effect through the code base.

When you add the @MainActor attribute to CalendarEngine, ensuring that all of its code is run on the main thread, suddenly every class that calls it needs to handle the fact that its methods are now async. So you update SyncAction. But that's used by ActionProcessor. Which is used by BackgroundTaskManager. Which has @objc methods for notification callbacks and actors can't have @objc methods.

So I sent Claude hacking away at it because it was a huge and tedious job, and 60 files and nearly 2,800 lines of code later, the damn thing wouldn't even compile. Everything was tangled up, and I couldn't tell if I was fixing things or just digging a deeper hole.

So I hit undo on the whole mess. Heart hands to git, saving my bacon as per usual.

A More Systematic Approach

So that's how I learned that you can't eat the entire Swift 6 concurrency elephant all at once. Every change affects other code, and the interactions become impossible to reason about. I couldn't ship this!

The right way is slow and steady: make one change, compile, test, commit, and repeat. Order matters, you have to start at the edges of your dependency tree and work your way in.

I created a phased plan:

Phase 0: (Probably) Zero-Risk Changes (get it?)

Some changes have no cascade effect at all. The @preconcurrency import attribute tells the compiler: "this module isn't Sendable-annotated yet, but let's trust Apple when we use it."

// BEFORE

import CoreData

// AFTER

@preconcurrency import CoreDataThis shuts up the warnings about CoreData types not being Sendable, and you don't have to touch anything else. I went through and slapped @preconcurrency on imports of Apple's system frameworks: CoreData, Combine, EventKit, and UserNotifications. The same worked fine for OpenTelemetry (the Honeycomb distro) which I use and love for optional diagnostic telemetry.

Similarly, adding Sendable conformance to immutable value types:

// Just add the conformance - no behavior change

public enum ProcessingMode: Sendable {

case background

case foreground

}

public struct BatteryAwareConfig: Sendable {

public let adaptBatchSize: Bool

public let respectLowPowerMode: Bool

public let minimumBatteryLevel: Double

}Just like that, about 50 warnings gone! No logic touched.

Phase 1: Leaf Node Actors

Next, I converted isolated components that don't have any or many dependencies. The trick here is that actors require await at every call site, so it's best to start with code that isn't called from many places.

BackgroundMetricsStore was a perfect candidate: a simple class with a dictionary protected by NSLock.

// BEFORE: Manual locking

public class BackgroundMetricsStore {

private var metrics: [UUID: BackgroundTaskMetrics] = [:]

private let metricsLock = NSLock()

public func recordStart(_ taskId: UUID) {

metricsLock.lock()

defer { metricsLock.unlock() }

metrics[taskId] = BackgroundTaskMetrics(startTime: Date())

}

public func recordEnd(_ taskId: UUID) {

metricsLock.lock()

defer { metricsLock.unlock() }

metrics[taskId]?.endTime = Date()

}

}

// AFTER: Actor isolation

public actor BackgroundMetricsStore {

private var metrics: [UUID: BackgroundTaskMetrics] = [:]

public func recordStart(_ taskId: UUID) {

metrics[taskId] = BackgroundTaskMetrics(startTime: Date())

}

public func recordEnd(_ taskId: UUID) {

metrics[taskId]?.endTime = Date()

}

}The actor version is cleaner, shorter, and, best of all, the compiler checks it for you. No lock to forget.

I turned three small services into actors at this stage, running the full test suite after each one. All green. Commit and move on.

Phase 2: The @MainActor Pattern

Many classes in iOS apps should run entirely on the main thread. ViewModels with @Published properties. Services that update the UI. Classes that use NotificationCenter observers with @objc selectors.

For these, a @MainActor decoration is the way to go:

@MainActor

class ActionsListViewModel: ObservableObject {

@Published var actions: [Action] = []

@Published var isLoading = false

private let actionStore: ActionStoreProtocol

func loadActions() async {

isLoading = true

actions = try? await actionStore.loadAll() ?? []

isLoading = false

}

}Here, the cascade is much more manageable than with actors, since SwiftUI views already run on the main actor. The ViewModel fits right in.

But there's a catch: test classes that create and use @MainActor objects need special handling. The setUp() and tearDown() methods of XCTestCase aren't main-actor-isolated, so you need to use the async variants:

@MainActor

final class ActionsListViewModelTests: XCTestCase {

var viewModel: ActionsListViewModel!

var mockStore: MockActionStore!

override func setUp() async throws {

try await super.setUp()

await MainActor.run {

mockStore = MockActionStore()

viewModel = ActionsListViewModel(actionStore: mockStore)

}

}

override func tearDown() async throws {

await MainActor.run {

viewModel = nil

mockStore = nil

}

try await super.tearDown()

}

}I updated 15 test files to use this pattern. It's a bit verbose for my liking, but it's clearer about thread safety, and the compiler keeps you honest.

Phase 3: The Tricky Bits

Not everything fits neatly into the actor or @MainActor pattern. Some code genuinely needs escape hatches.

The Singleton Problem

Singletons are common in iOS code, and they pose a problem for Swift 6: a static let property creates a race condition if the singleton isn't Sendable.

public class PersistenceController {

public static let shared = PersistenceController() // Warning!

// ...

}The warning says: "static property 'shared' is not concurrency-safe because non-'Sendable' type 'PersistenceController' may have shared mutable state."

The compiler is right to worry. But if you know your singleton is thread-safe (because, say, NSPersistentContainer manages its own thread safety), you can tell the compiler to trust it with nonisolated(unsafe). I went for copious "justification" comments so we can audit these things in the future:

public class PersistenceController {

// nonisolated(unsafe) justification:

// 1. Static let initialization is thread-safe (dispatch_once semantics)

// 2. NSPersistentContainer manages its own queue-based isolation

// 3. All context operations use performAndWait/perform

public nonisolated(unsafe) static let shared = PersistenceController()

}The Non-Sendable Framework Type Problem

Some types from Apple's frameworks aren't Sendable. EKCalendar from EventKit is a prime example. You can't pass an EKCalendar across actor boundaries.

My original calendar cache implementation mistanekly stored full EKCalendar objects:

actor CalendarCacheActor {

private var cache: [String: EKCalendar] = [:] // Error! EKCalendar isn't Sendable

func get(_ identifier: String) -> EKCalendar? {

return cache[identifier]

}

}The solution was to rethink what the cache actually needed to do. It turned out we only used the cached calendars for title lookups and titles are strings, which are Sendable.

So instead:

actor CalendarCacheActor {

private var cache: [String: CachedCalendarMetadata] = [:]

func getTitle(_ identifier: String) -> String? {

guard let entry = cache[identifier] else { return nil }

if entry.isExpired {

cache.removeValue(forKey: identifier)

return nil

}

return entry.title

}

}

struct CachedCalendarMetadata: Sendable {

let identifier: String

let title: String

let timestamp: Date

var isExpired: Bool {

timestamp.addingTimeInterval(300) < Date() // 5 minute TTL

}

}If I ever need a real EKCalendar object, I just fetch it fresh from EKEventStore.calendar(withIdentifier:). EventKit keeps calendars in memory so it's quick and makes full caching of this data totally redundant and silly. And now since I'm not passing EKCalendar across actor boundaries, the compiler doesn't complain.

The @objc Compatibility Problem

The BackgroundTaskManager class was the hardest service to convert because it has @objc methods for notification callbacks:

@objc private func handleSignificantTimeChange(_ notification: Notification) {

// Process time change

}Actors can't have @objc methods, so it couldn't become an actor. The fix was to decorate it with @MainActor, which does play nicely with Objective-C. All notification callbacks already run on the main thread, so marking the class @MainActor accurately describes its actual behavior:

@MainActor

public class BackgroundTaskManager: NSObject {

// @objc methods work fine here

@objc private func handleSignificantTimeChange(_ notification: Notification) {

// Still on main thread, compiler verifies this

}

}Phase 4: Enabling Swift 6

After all the incremental changes, turning on Swift 6 mode was almost anticlimactic. As soon as I flipped this switch, it also enabled Strict Concurrency Checking: Complete which is the default value.

- SWIFT_VERSION = 5.0;

+ SWIFT_VERSION = 6.0;Three new warnings popped up—all in test code, all easy to fix, but otherwise the build was clean. Playing around in the simulator, everything felt like the same code and everything still worked - or so I thought (foreshadowing).

Trust, But Verify (with Thread Sanitizer)

Swift 6's compile-time checks are remarkable, but they're not perfect. Some patterns can't be verified statically. And for code that uses escape hatches like nonisolated(unsafe), you're back to runtime verification.

Thread Sanitizer (TSan) is the tool for this. It instruments your code at runtime and catches data races as they happen.

I turned on TSan by passing the following flag to xcodebuild (you can also teach the excellent xcodebuildMCP to use it):

xcodebuild -enableThreadSanitizer YESThen I ran the full test suite of 531 tests, including the UI tests. This uncovered one issue: in a mock class used for testing, a static property was being accessed from multiple threads:

// BEFORE

class MockEventStore: EKEventStore {

static var mockAuthorizationStatus: EKAuthorizationStatus = .fullAccess // Race!

}

// AFTER

class MockEventStore: EKEventStore {

// nonisolated(unsafe) - test-only mutable state, each test controls its value

nonisolated(unsafe) static var mockAuthorizationStatus: EKAuthorizationStatus = .fullAccess

}With that done and dusted, TSan showed zero data races anywhere in the test suite.

Deploying to a Real Device

Here's where I ran into trouble again: Swift 6's compile-time checks can't see across framework boundaries.

When your code interacts with Objective-C frameworks that deliver callbacks on arbitrary threads (like NotificationCenter, BGTaskScheduler, and CoreData) the compiler can't verify which thread will invoke your closure. Swift 6 includes runtime checks that verify actor isolation when closures are invoked. If those checks are violated, you immediately get a crash:

Exception Type: EXC_BREAKPOINT (SIGTRAP)

Termination Reason: SIGNAL 5 Trace/BPT trap: 5

Thread 8 Crashed:

0 libdispatch.dylib _dispatch_assert_queue_fail

...

5 CalCopilot closure #1 in CloudKitSyncMonitor.setupNotifications()

The crash is dispatch_assert_queue_fail is Swift 6's runtime's verification that code is running on the expected actor.

These crashes are easy to spot—they happen right away when you hit the right code path. Unfortunately things like Background Refresh, Notifications and CloudKit aren't testable in the Simulator and therefore you really need a real iOS device to shake them out. Don't wait until you've pushed it out to your beta testers on TestFlight!

The Combine Publisher Problem

My CloudKitSyncMonitor class was marked @MainActor, and it used Combine to subscribe to CoreData notifications:

@MainActor

public class CloudKitSyncMonitor: ObservableObject {

private func setupNotifications() {

NotificationCenter.default.publisher(for: .NSPersistentStoreRemoteChange)

.sink { [weak self] notification in

Task {

await self?.handleRemoteChange(notification)

}

}

.store(in: &cancellables)

}

}Whoops, CoreData posts .NSPersistentStoreRemoteChange from a background thread. The Combine sink closure runs on whatever thread delivers the notification. That closure grabs self, which is @MainActor isolated. Swift 6 checks if the closure is running on the main actor and if itsn't them kablammo, you get another crash.

The compiler can't catch this, because Combine's type signatures don't say anything about actor isolation. It just sees a sink closure grabbing @MainActor state, but it has no idea that NotificationCenter might call that closure from a background thread. This is where Swift's static checks run into Objective-C's “anything goes” runtime.

Once you see what's going on, the fix is pretty easy:

// BEFORE: can be called on any thread

NotificationCenter.default.publisher(for: .NSPersistentStoreRemoteChange)

.sink { [weak self] notification in

Task {

await self?.handleRemoteChange(notification)

}

}

.store(in: &cancellables)

// AFTER: explicitly set .receive(on:...) main thread

NotificationCenter.default.publisher(for: .NSPersistentStoreRemoteChange)

.receive(on: DispatchQueue.main) // Hop to main thread BEFORE the sink

.sink { [weak self] notification in

Task {

await self?.handleRemoteChange(notification)

}

}

.store(in: &cancellables)The .receive(on: DispatchQueue.main) makes sure the sink closure runs on the main thread before it touches any @MainActor state.

The same pattern applies to @objc notification handlers:

@MainActor

public class CalendarChangeNotificationManager: ObservableObject {

// BEFORE: @objc method can be called from any thread

@objc private func eventStoreChanged(_ notification: Notification) {

changeCount += 1 // Mutating @MainActor state from background thread!

}

// AFTER: Dispatch to MainActor first

@objc private func eventStoreChanged(_ notification: Notification) {

Task { @MainActor in

self.handleEventStoreChangeOnMainActor()

}

}

private func handleEventStoreChangeOnMainActor() {

changeCount += 1 // Safe - guaranteed to be on MainActor

}

}The Closure Isolation Inheritance Problem

We weren't crashing at launch anymore, great! But overnight testing revealed more crashes. All happening when the app ran background tasks. It turns out that in Swift 6, closures take on the actor isolation of wherever you define them.

Take the following code. The compiler won't flag it and it'll never fail in a simulator, but as soon as you call it from a background thread in the real world it'll crash:

@MainActor

class MyClass {

func setupCallback() {

// This closure is defined inside a @MainActor method

someFramework.onCallback {

// Swift 6 considers this closure @MainActor-isolated!

// If the framework calls it from a background thread kaboom!

}

}

}The crash occurs before any code in the closure runs. Swift 6 checks isolation as soon as the closure is called. If a @MainActor closure runs off the main thread, the app crashes immediately.

This is different from the Combine and NotificationCenter examples, where the issue was accessing @MainActor state from a background thread. In this case, the closure itself is marked as @MainActor, regardless of its contents.

Adding Task { @MainActor in } inside the closure doesn't help. Instead, you have to define the closure in a nonisolated context, so it doesn't inherit any actor isolation:

// BEFORE - this will crash

someFramework.onCallback {

Task { @MainActor in // Doesn't matter - crash happens before this line

self.doWork()

}

}

// AFTER

@MainActor

class MyClass {

func setupCallback() {

// Delegate to nonisolated static method

Self.registerCallback()

}

// Closure defined here is nonisolated - no actor inheritance

nonisolated static func registerCallback() {

someFramework.onCallback {

// This closure is nonisolated - safe to call from any thread

Task { @MainActor in

await MyClass.shared.doWork() // NOW the hop to MainActor works

}

}

}

}The Sequel: Background Task Callbacks

Thread 4 Crashed:

0 libdispatch.dylib _dispatch_assert_queue_fail

...

5 CalCopilot closure #1 in BackgroundTaskManager.registerBackgroundTasks()

7 BackgroundTasks __41-[BGTaskScheduler _runTask:registration:]_block_invoke_5

Same pattern, different framework. BGTaskScheduler runs its task callbacks on a background queue, not the main thread. The class was @MainActor isolated, and the callbacks captured [self]:

@MainActor

public class BackgroundTaskManager {

func registerBackgroundTasks() {

BGTaskScheduler.shared.register(

forTaskWithIdentifier: "com.app.refresh",

using: backgroundQueue

) { [weak self] task in // This closure runs on backgroundQueue!

Task { @MainActor in

self?.handleTask(task) // Crashes before we even get here

}

}

}

}I hoped that weakly capturing self ([weak self], my new band name) would be enough. But no because in Swift 6, even a weak capture of self triggers an actor isolation check as soon as the closure starts before the Task even runs. If the closure gets called on a background thread, then Swift 6 sees a closure grabbing @MainActor state from the wrong place.

This wisdom comes from the Swift Migration Guide: Closures capture the actor isolation of their surrounding context by default.

Because registerBackgroundTasks() is a @MainActor method, the closure defined inside it inherits @MainActor isolation. BGTaskScheduler calls this closure from a background thread. Swift 6's runtime checks see a @MainActor-isolated closure being invoked off the main thread and crashes before the closure even executes any code. Task { @MainActor in } inside the closure doesn't help either, again because the crash happens as soon as the closure is called, not inside the Task.

The Fix: Define Closures in Nonisolated Context

Move closure definitions to nonisolated static methods. Closures defined in a nonisolated context don't inherit actor isolation:

@MainActor

public class BackgroundTaskManager {

public func registerBackgroundTasks() {

// Delegate to nonisolated static method to avoid closure isolation inheritance

Self.performTaskRegistration(

backgroundQueue: backgroundQueue,

processingId: Self.processingTaskIdentifier,

refreshId: Self.refreshTaskIdentifier

)

}

// Closures defined HERE are nonisolated - no actor inheritance

nonisolated static func performTaskRegistration(

backgroundQueue: DispatchQueue,

processingId: String,

refreshId: String

) {

BGTaskScheduler.shared.register(

forTaskWithIdentifier: processingId,

using: backgroundQueue

) { task in

// This closure is nonisolated - safe to call from background thread

handleProcessingTaskFromBackground(task)

}

}

nonisolated static func handleProcessingTaskFromBackground(_ task: BGTask) {

// Hop to MainActor for ALL work - including logging, type checking, everything

Task { @MainActor in

shared.handleProcessingTask(task)

}

}

}The same applies to task.expirationHandler, which also runs on a background thread:

// BEFORE - closure inherits @MainActor isolation

task.expirationHandler = { [weak self] in

self?.handleExpiration() // Crash!

}

// AFTER - define in nonisolated context, hop to MainActor inside

nonisolated static func setExpirationHandler(for task: BGTask) {

task.expirationHandler = {

Task { @MainActor in

shared.handleExpiration()

}

}

}Remember, the closure should do nothing except call the handler. Even something like Logger.shared.error() can cause problems if Logger touches any @MainActor state. Put all the real work, like logging, type checking, and error handling, inside the Task { @MainActor in } block.

The Gotchas Checklist

After enabling Swift 6, grep your codebase for these patterns:

- Combine

sinkclosures in@MainActorclasses (add.receive(on: DispatchQueue.main)) @objcmethods in@MainActorclasses that mutate state (dispatch to MainActor first)BGTaskScheduler.registercallbacks (move closure tononisolated staticmethod)task.expirationHandlerclosures (same pattern)- Any callback-based API where you're not certain which thread delivers the callback

So what can I get away with safely?

Don't panic and start ripping out every [weak self] in your codebase. The important thing is to understand why the crashes happened. Swift 6 checks actor isolation when a closure is called, not when you access self. These crashes happened because closures that grabbed @MainActor state got called from background threads.

These patterns are safe for @MainActor classes:

| Pattern | Why It's Safe |

|---|---|

Timer.scheduledTimer from @MainActor method |

Timer fires on the run loop where it was scheduled (main) |

Timer.publish(on: .main) |

Explicitly publishes on main run loop |

NotificationCenter.addObserver(queue: .main) |

Explicitly delivers on main queue |

DispatchQueue.main.asyncAfter |

Explicitly runs on main thread |

@Published property in @MainActor class |

Can only be set from MainActor, so publishes on MainActor |

These patterns are unsafe:

| Pattern | Why It Crashes |

|---|---|

NotificationCenter.default.publisher().sink |

Framework posts from arbitrary threads |

BGTaskScheduler.register(using: backgroundQueue) |

Explicitly background queue |

task.expirationHandler |

System calls from background thread |

| Any delegate callback without thread guarantee | Framework decides the thread |

The real trick is paying attention to where the closure runs, not just what it captures. If you know the closure runs on the main thread, grabbing @MainActor state is totally fine.

The Numbers

The final migration touched 79 files and changed approximately 2,800 lines of code and markdown docs. Here's the breakdown:

Files Modified by Category:

- Production services: 32 files

- ViewModels: 6 files

- Models and types: 8 files

- Unit test files: 28 files

- UI test files: 5 files

Patterns Applied:

@preconcurrency import: 30 files@MainActorclasses: 18 classesactortypes: 3 typesSendableconformance: 25 typesnonisolated(unsafe)escape hatches: 15 instances (all documented)

Test Results:

- 531 tests passing

- 0 Thread Sanitizer warnings

- 0 runtime data races detected

What I Learned

The compiler is on your side, not out to get you. Those 168 errors in my first try weren't just roadblocks; they were the compiler pointing out every spot where I might have a data race. Once I realized that, I stopped fighting the errors and started paying attention.

Order matters a lot. Starting with the leaf nodes instead of the core services made the cascade manageable. If I'd been methodical from the beginning, I probably could have finished in a week instead of three.

Use escape hatches judiciously. nonisolated(unsafe) and @unchecked Sendable aren't giving up but they also shouldn't be your default go-to; they're for the rare case when you know something the compiler can't. Study your code and see if there isn't a better way to do things first, but if you can't then write down your reasoning, and always double-check with Thread Sanitizer.

Tests need just as much care as production code. I spent a bunch of time updating test files. Test code has all the same concurrency headaches, maybe even more, since tests often create and mess with objects across setup, execution, and teardown.

Framework boundaries are where things get tricky. Swift 6 can check your Swift code, but it can't see into Objective-C frameworks. When NotificationCenter, Combine publishers, or delegate callbacks fire on background threads, you have to jump to the main actor before touching @MainActor state. The compiler won't warn you, but running on a real device will catch it immediately.

Closure isolation inheritance is sneaky. Closures you define inside @MainActor methods pick up that isolation. If a framework calls those closures from a background thread, you crash. The fix is to define closures in nonisolated static methods, and do all the real work inside Task { @MainActor in }.

You can't catch everything with simulators and TSan, so make sure to do perform thorough functional testing on real devices that have iCloud, background refresh, notifications, etc. No matter how careful you are with static checks, runtime testing catches what the compiler misses.

I got lucky with 3rd-party frameworks because the only one I'm using is OpenTelemetry. Slapping @preconcurrency on import OpenTelemetry let me continue on with OTel autoinstrumentation and logging, but I did have to comment out some custom tracing instrumentation because OpenTelemetry's Span type wasn't Sendable at the time of writing.

Was It Worth It?

Ultimately I think so, yes. I'm back to shipping with high confidence, even more than before considering that I didn't know nearly enough about concurrency in Swift when I first started. I can confidently add code and know that if I've done something bad then the compiler will most likely let me know, and if not then I'll catch it quickly soon after.

It feels pretty good knowing that every possible data race in my codebase is either proven safe by the compiler or clearly and carefully marked as "trust Apple, they know what they're doing" with nonisolated(unsafe). Now my test suite always runs with Thread Sanitizer before I ship any code.

Swift 6's concurrency checking is a huge safety upgrade, but it's a lot of work to adopt, especially in an existing codebase. But the end result is code that's provably correct in ways that just weren't possible before.

Irving Popovetsky is Director of Customer Architecture at Honeycomb.io, where he helps engineering teams understand their systems through observability. Calendar Copilot, the calendar automation app discussed in this post, is his side project for learning iOS development. You can download it here.